How to train and bring acoustic AI to a real electronic device

Abstract

Detecting acoustic events in real-world environments is a much more complex challenge than “recognizing sounds.” In industrial, urban, or environmental settings, events overlap, noise is persistent, and conditions are constantly changing. Solving this problem requires artificial intelligence systems capable of simultaneously modeling time, frequency, and context, and doing so reliably outside the laboratory.

This article traces the design and evolution of a deep learning-based acoustic event detection system, from the definition of the problem to its implementation in a real electronic device. Previous experience with acoustic bird detection systems, deployed in remote and energy-constrained environments, had naturally led to a preference for small models and low-power architectures. In that context, autonomy was the dominant variable, and model complexity had to be subordinated to it.

In this project, the scenario changes. In industrial applications, energy consumption is no longer a critical constraint and acoustic complexity increases significantly: more sources, more overlaps, and greater operational variability. This change in context enables—and demands—a different approach: large models, real computing power, and non-trivial engineering decisions, implemented on dedicated, autonomous, low-cost electronic equipment, without resorting to a general-purpose computer as a hardware platform.

Three central themes are explored along the way: the choice of deep architectures inspired by DCASE—combining convolutional networks and Transformers—the practical limits of training acoustic AI for real-world scenarios, and, above all, the real bottleneck of the system: the dataset. When real data is insufficient, carefully designed synthetic generation ceases to be an alternative and becomes a structural part of the training process.

Rather than presenting a model, the article shows how to build a complete and reusable pipeline, where data, labels, training, and hardware deployment form a coherent system. This approach capitalizes on previous experience and allows acoustic AI to be taken from prototype to device, and from the laboratory to the real world.

When the problem requires large models and synthetic datasets

Automatic acoustic event detection is a much more complex problem than it seems at first glance. It is not just a matter of “recognizing sounds,” but of identifying temporal and spectral patterns in real scenarios, with noise, overlaps, and constant variations in the environment.

This project was born with a clear objective: to detect and classify complex sound events in a specific environment, executing all processing locally on a Raspberry Pi-type platform. From the outset, it was clear that this was not a low-power device, nor a typical microcontroller application: the complexity of the problem required more robust models and real computing power, while maintaining dedicated, low-cost, purpose-built electronics, without resorting to a general-purpose computer as the hardware platform.

The starting point: a real acoustic problem

The chosen setting was an industrial environment, characterized by:

- Broad spectrum machinery

- Continuous sounds mixed with transient events

- Frequent overlap between sources

- Changes in regime and load

- Persistent background noise

In this context, simple audio classification techniques are insufficient. It is not enough to detect energy or static patterns: it is necessary to model the time, frequency, and coexistence of events.

Why large models? CNN14 + Transformers

From the outset, lightweight architectures were ruled out, as the problem required an approach comparable to that used in academic research and benchmark competitions. The conceptual framework of the project relied heavily on DCASE (Detection and Classification of Acoustic Scenes and Events), an international initiative that defines benchmarks, datasets, and representative tasks for acoustic analysis in real-world conditions.

The experience accumulated in DCASE shows that simple models are not sufficient for detecting realistic acoustic events. Deep convolutional networks (CNNs) are necessary to capture complex spectral structures in spectrograms; temporal modeling is key to understanding how these patterns evolve over time; and attention mechanisms, together with Transformer-based architectures, allow the model to focus on relevant audio fragments, significantly improving performance in the face of events of varying duration, overlapping events, or events immersed in background noise.

Chosen architecture

The central model of the project combines:

- CNN14 as a time-frequency feature extractor.

- Transformer blocks to model long temporal dependencies.

- Attention mechanisms to weight relevant regions of the audio.

- Configurable outputs for multi-class classification or event detection.

This type of architecture is computationally expensive, but necessary when seeking true robustness.

The real challenge: the dataset

The real bottleneck was the dataset; the model wasn't the biggest problem.

Initial difficulties

- Few real audio recordings available per class.

- Little variability in recording conditions.

- Lack of examples with overlapping events.

Training a large model with a small dataset is not only inefficient: it's counterproductive.

Generating synthetic data: a key decision

The solution was to design a controlled and reproducible synthetic audio generation pipeline.

Adopted approach:

- Domain selection

An environment (e.g., industrial) was explicitly defined to maintain acoustic consistency. - Real base audio

Real recordings of machines and events served as seeds. - Augmentation at the waveform level

Thousands of synthetic audio files were generated by applying random combinations of:- Noise

- Gain changes

- Equalization

- Compression

- Reverberation

- Temporal cuts

- Time shifts

- Mixing of sources

Audio files were created with multiple simultaneous events, simulating real conditions where several machines operate at the same time.

Labeling and control: CSV as a source of truth

Each audio file generated was associated with a CSV file of labels, which allows us to:

- Maintain traceability of the dataset

- Define single or multiple labels

- Retrain models with different strategies

- Audit errors and false positives

The CSV became the core of the training system, clearly separating data, labels, and configuration.

Representation and training

The audio files are transformed into log-mel spectrograms, following standard practices in DCASE and academic literature.

About this representation:

- Deep models are trained for tens or hundreds of epochs.

- Metrics beyond accuracy are monitored.

- Confusion and degradation in the face of interference are analyzed.

One of the most important lessons learned was understanding that certain errors are not bugs, but physical limitations: spectral masking also exists for models.

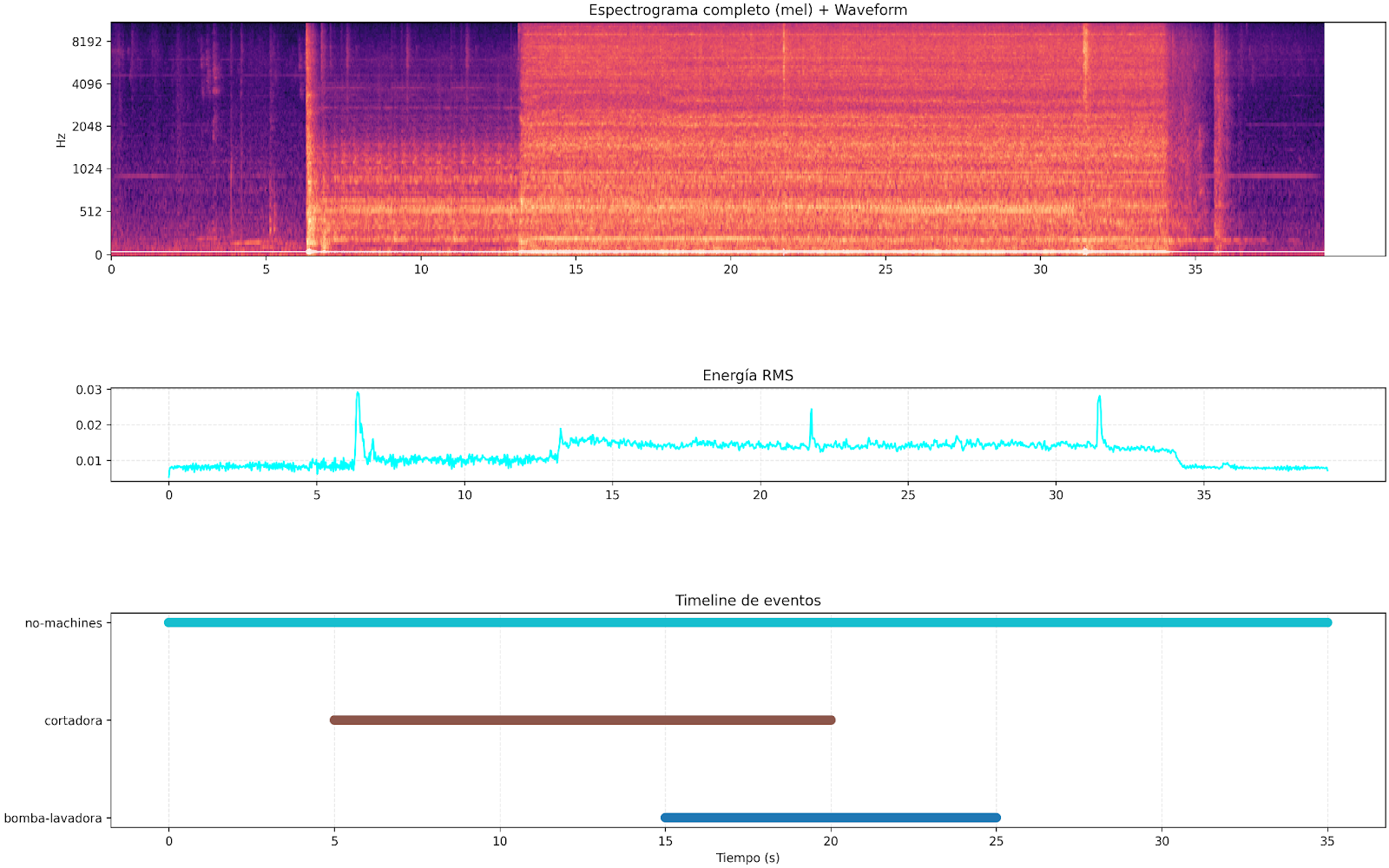

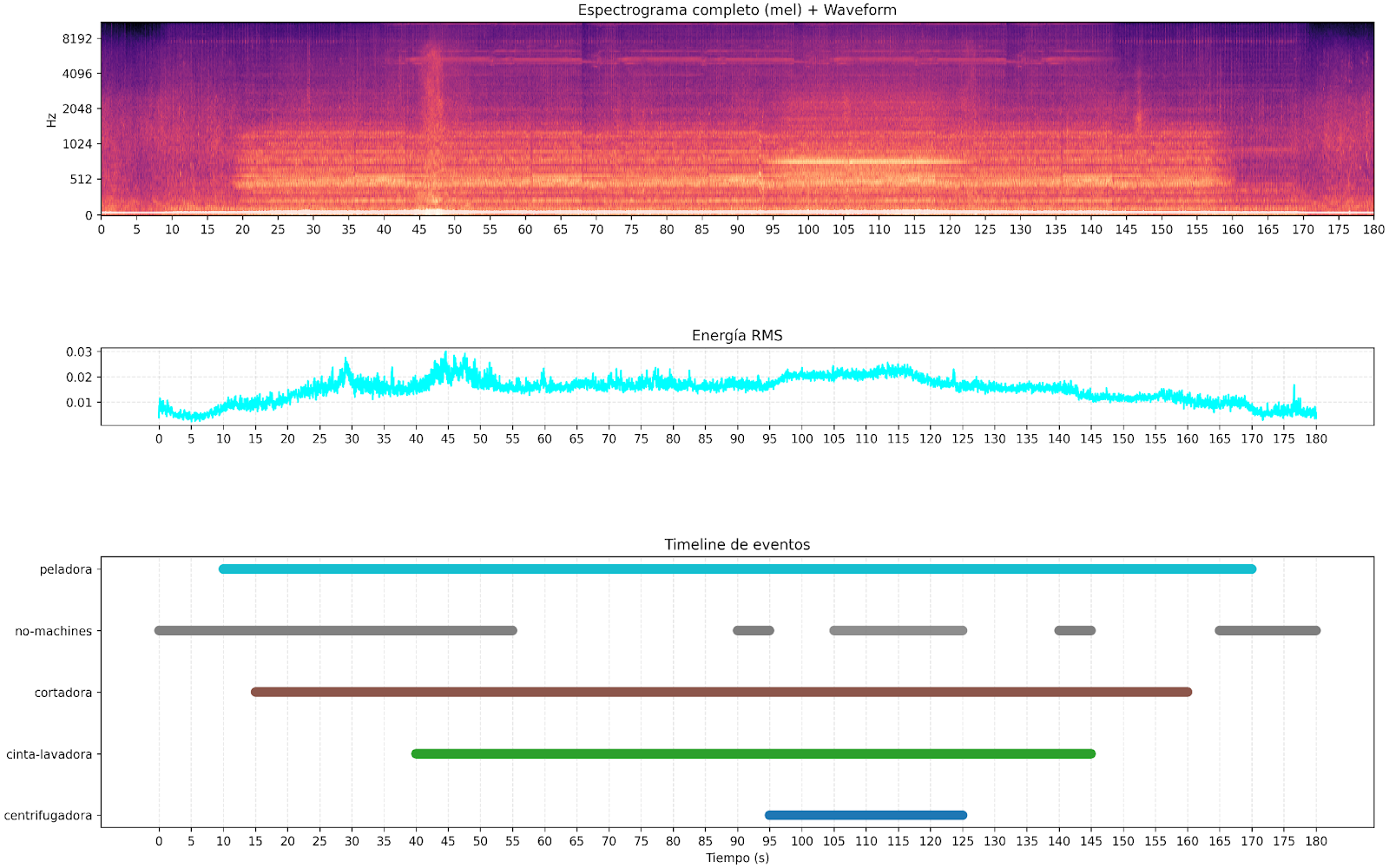

The following figures show specific examples of the type of information processed and generated by the system. The upper part shows the complete log-mel spectrogramof the audio, where persistent spectral patterns and variations over time can be seen, typical of an environment with multiple active sound sources. Below is the RMS energy, which reflects the overall evolution of the audio power, but which alone does not allow us to discriminate which events are occurring. Finally, the bottom timeline summarizes the result of the model's inference, indicating which acoustic events were detected in each time interval. This visualization highlights one of the central motivations of the project: while simple metrics such as energy are not sufficient to separate overlapping sources or events, the model based on CNN, attention, and Transformers manages to identify and segment different acoustic events even when they coexist in the same audio.

Results and lessons learned

This project yielded several clear conclusions:

- Real-world acoustic problems require large models.

- The dataset defines the performance ceiling much more than the architecture.

- Well-designed synthetic generation is a powerful tool.

From a specific case to a reusable approach

Although the project was born in a specific environment, the end result is a generic acoustic event detection pipeline, adaptable to:

- Industrial environments

- Urban settings

- Environmental monitoring

- Security

- Acoustic research

By changing the domain of the dataset, the same approach can be reused without touching the base architecture.

Written by Alejandro Casanova.

For further inquiries, contact us: info@emtech.com.ar